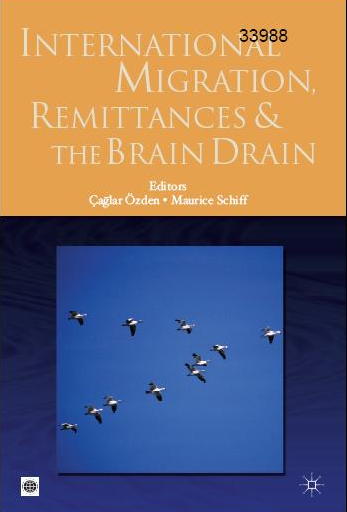

International Migration, Remittances, & The Brain Drain

The World Bank released a timely report this week on the topic of migration and its effects on world development. The study's findings point to a worrying pattern of "brain drain" - In other terms, the flight of skilled middle-class workers who could otherwise help lift their countries out of poverty. Although the exact effects are still not completely understood, there is a growing sense among economists that such migration plays a crucial role in a country's ability to pursue sustainable development.

The World Bank released a timely report this week on the topic of migration and its effects on world development. The study's findings point to a worrying pattern of "brain drain" - In other terms, the flight of skilled middle-class workers who could otherwise help lift their countries out of poverty. Although the exact effects are still not completely understood, there is a growing sense among economists that such migration plays a crucial role in a country's ability to pursue sustainable development.From the NYT:

The study found that from a quarter to almost half of the college-educated citizens of poor countries like Ghana, Mozambique, Kenya, Uganda and El Salvador lived abroad in an O.E.C.D. country - a fraction that rises to more than 80 percent for Haiti and Jamaica. In contrast, less than 5 percent of the skilled citizens of the powerhouses of the developing world, like India, China, Indonesia and Brazil, live abroad in an O.E.C.D. country.

These patterns suggest that an extensive flight of educated people is damaging many small to medium-size poor countries, while the largest developing countries are better able to weather relatively smaller losses of talent, and even benefit from them when their skilled workers return or invest in their native lands.

Most experts agree that the exodus of skilled workers from poor countries is a symptom of deep economic, social and political problems in their homelands and can prove particularly crippling in much needed professions in health care and education. But some scholars are asking whether the brain drain may also fuel a vicious downward cycle of underdevelopment - and cost poor countries the feisty people with the spark and the ability to resist corruption and incompetent governance.

Devesh Kapur and John McHale argue in their book, "Give Us Your Best and Brightest," published last week by the Center for Global Development, a research group in Washington, that the loss of institution builders - hospital managers, university department heads and political reformers, among others - can help trap countries in poverty. "It's not just the loss of professionals," said Mr. Kapur, an associate professor of government at the University of Texas at Austin. "It's also the loss of a middle class."

"The labor forces in many developed countries are expected to peak around 2010. Conversely, the labor forces in many developing countries are expanding rapidly. This imbalance is likely to create strong demand for workers in developed countries' labor markets, especially for numerous service sectors that can only be supplied locally." - International migration, remittances, and the brain drain, World Bank, 2005.