1979: A Year to Remember in the Struggle against Militant Islam

INTRODUCTION

Thomas Jefferson once professed: “I like the dreams of the future better than the history of the past.” In reviewing the lessons of history we find both solace and nuisance in the actions of those who came before us. Their actions set realities that we must confront in order to sustain us as the temporary custodians of human destiny. The recent uprising of ‘Islamic’ movements around the world should not come as a surprise to any objective historian. Although many in the public policy community continue to ponder the causes of ‘Islamic’ terrorism, one may find it helpful to use history as a guide in order to better understand what has become our existing reality. Many are quick to assert today that the biggest challenges facing humanity are terrorism and Weapons of Mass Destruction. Although I do not disagree that these two issues are of great importance to global security today, I offer that our most endearing challenge as human beings is understanding the depths of our ignorance.

An old saying holds that those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it. In facing threats to human freedom and dignity, we must understand our past failures and ensure that our chosen course serves the long-term interests of humanity despite our selfish impulses. It is in that spirit that I write these lines, not to cast blame but rather to contribute to a much needed debate on the future of human thinking on the matters of peace and international security.

In reviewing the contemporary history of the Middle East, I was particularly struck by the culmination of events that took place in 1979. I believe that year to be a remarkable year in the modern history of the Middle East and I believe it to be of particular relevance to the ongoing global fight against Middle Eastern terrorism. 1979 is both a year of peace and war. It is a year that saw the signing of a peace agreement between Israel and Egypt, a year when an ‘Islamic’ revolution succeeded in Iran, and a year that ended with the Soviet Union invading Afghanistan. These three events alone had profound implications on the rise of ‘Islamic’ militancy in the Middle East. 1979 was also a year of memorable names succeeding to power, one through a revolution, the other through an authoritative power grab, and the third through democratic elections. They are Khomeini in Iran, Saddam Hussein in Iraq, and Margaret Thatcher in Britain. With all the turmoil that marked 1979, we sometimes find solace in knowing that it was during that year that the selfless and enduring Mother Theresa won a Nobel Peace prize.

The Iranian Revolution: The beginnings of an internal cold war within Islam

1979 started with a bang when the U.S.-backed Shah of Iran was forced to flee to Egypt following a year of turmoil in Iran, a country he ruled with an iron fist for over 25 years. The Shah had seized power following the U.S.-sponsored overthrow of the Mossadeq government in 1953. On 1 February 1979, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini returned to jubilating masses after 15 years in exile, thus, marking the first successful ‘Islamic revolution’ against a Western-installed ruler in the post-colonial history of the Middle East.

The immediate and sustained response to the Iranian revolution by pro-Western Arab regimes was fairly consistent in that it relied on both a systematic crackdown on Islamic elements, political dissenters, and those sympathetic to the Khomeini regime, and a heavy propaganda campaign, the latter being nuanced and refined to reflect local political, cultural, and social dimensions. What were pro-Western Arab regimes frantically concerned about, one may ask: (1) the precedent of a successful ‘Islamic’ revolution toppling a Western-backed monarchy; (2) the expressed intent of the Khomeini regime to export his ‘revolutionary Islamic’ ideology; and (3) the now-perceived inability of the West in general, and the U.S. in particular, to protect them from their own disgruntled populations. The first of these fears became reality for Saudi Arabia when on 20 November 1979 some 200 ‘Islamic militants’ seized the Grand Mosque in Mecca, taking hundreds of pilgrims hostage.

In short, 1979 marked the beginning of a regional war between a Saudi-led coalition of Sunni Arab regimes and the Shiite-led revolution of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. In the Middle East, this internal struggle was of critical importance to the Cold War because it introduced new variables in the two superpowers’ designs for influence in the region.

Furthermore, the conflict between Khomeini’s Iran and many Sunni Arab regimes exasperated to what became a direct military conflict between Iraq and Iran. Iraq was provided financial and military support by its rich Gulf neighbors, and to some extent by the U.S. despite the fact that the Iraqi regime had aligned itself with the Soviets as a member of Nasser’s Arab nationalist club. One important thing to note about 1979 also is that on 16 July of that year, the infamous Saddam Hussein replaced Hassan Al-Bakr as president of Iraq.

In Saudi Arabia, the urgency of the altered power dynamic in the Middle East caused by the Iranian revolution was of particular importance. The financial capacity of the country’s oil resources, its control over two of the holiest shrines in Islam (The Kaaba in Mecca and the holy mosque in Medina), and the ‘friendly’ status it enjoyed in the West, offered the Saudi regime invaluable assets as a power broker in the internal cold war within Islam. In addition to the generous support the kingdom lent to Iraq in its war against Iran, the Saudis operated another track in countering Khomeini’s ideological exports. They unleashed their own ideological WMD: another brand of Islamic extremism, the Salafist doctrine.

The Israeli-Egyptian peace agreement: The mishandling of Arab public opinion

On 26 March 1979, Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat signed a historic peace accord on the North Lawn of the White House, marking the successful end of a negotiation process that had started some 16 months earlier. Many, including myself, hail such agreement as a courageous step towards peace. The fact that Israel was willing to undermine the expansionist agenda of some of its ardent supporters by evacuating Jewish settlements in the Sinai and returning sovereignty of the latter to Egypt along with Egypt’s recognition of Israel as a sovereign Jewish state by agreeing to formal diplomatic relations is historically significant. However, the positive energy that many intellectuals expected to be generated by such an agreement was not all that positive in that it cost Anwar Sadat his life and provided up-and-coming Islamic factions with added fuel for their propaganda and recruitment efforts.

The historic handshake of 1979, for many in the West, symbolized the success of pragmatism over political fantasy; the beginning of peaceful coexistence between Israel and its Arab neighbors. For many in the Middle East, however, that same handshake symbolized the defeat of Arab nationalism. Recall that Egypt under Nasser was the center of the Arab Nationalist agenda. By signing a peace agreement with Israel, Sadat was seen by many in the Arab streets as having betrayed the ‘Arab cause’. The Palestinians felt particularly betrayed because they saw their coalition of Arab Nationalist defenders crumble, as well as a major territorial dispute taken off the claim list in the Arab-Israeli conflict. This was further dramatized when a group of Palestinians held Egyptian diplomats, including the Egyptian Ambassador to Turkey, hostage in Ankara on 13 July 1979.

Following the peace agreement, the disenchantment in the streets of Egypt and other pro-Western Arab countries was quelled through repressive police actions that further inflamed emotions and degraded human rights and civil liberties. Instead of promoting a constructive domestic dialogue, the pro-Western Arab regimes rejected dissent and chose by their own actions to leave a rising ‘Islamic’ militancy room for credibility and appeal. Those regimes effectively confined a very important debate to the dark rooms of the underground militancy movement, thus, undermining their already-frail legitimacy and setting political Islam on the track of becoming a viable alternative for their disgruntled populations.

The Soviet Invasion of Afghanistan: The making of a global militant force

On the Christmas Eve of 1979, capping what was a remarkable year in the contemporary history of the Muslim World, the Soviet Union decided to bring its sleighs of fire into Afghanistan. This particular event was largely framed within the context of the Cold War; the battle of the world’s two superpowers for strategic domination. One serious casualty of such approach is its gasping lack of understanding of the forces at play. The exasperating shortsightedness of the U.S. policies that went into effect in forming a resistance force to counter the Soviet aggression is particularly worthy of notice.

The U.S. government responded to the Soviet invasion immediately with expressions of outrage and calls for redress. When its calls were not heeded, the U.S. went into action by sponsoring both covert and overt efforts aiming to guarantee Soviet defeat in Afghanistan. One important thing to note at this point is that in this same year (1979), the conservatives had taken control of the British Parliament and Margaret Thatcher was elected Prime minister of Britain. A year later, Ronald Reagan beat Jimmy Carter to the White House marking the beginning of a conservative Western front against the Soviets. In short, the heat index of the Cold War had just jumped up a few points as the Soviets decided on their Afghanistan adventure all while significant political changes were taking place in both Britain and the U.S.

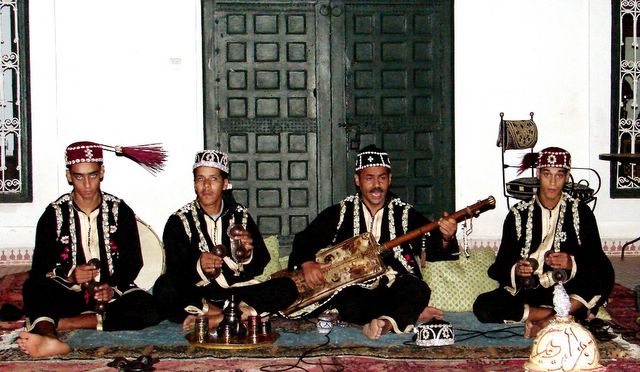

One of the covert policies of the U.S. in Afghanistan was the logistical support of the Mujahideen force, which included large numbers of Arab fighters who went to Afghanistan to conduct ‘Jihad’ against the ‘God-less’ Soviets. Young Arab fighters flocked in from every country in the Middle East. They were supported and trained in a large part by Saudi-backed organizations, many of which are now subject to terrorism funding investigations. The ability of these organizations to have (1) Official backing from several Arab governments, the most notable being the Saudi regime, (2) Freedom of operation within the global financial network, and (3) fertile ground for recruitment and fund-raising, was central to their success. It is during those times that such organizations perfected the art of money-laundering and the seamless transfer of funds across financial networks.

In many ways Afghanistan, because of the Soviet invasion, has become the first multinational staging ground for the global Muslim terrorism we witness today. Afghanistan provided the Islamic militancy with the pre-requisites it needed for the creation of a global army. Afghanistan gave them a cause, an ideology, a sense of brotherhood and unity, along with military training and real combat experience. These armies had access to weapons and training from western elites and money was no object. Unfortunately, no one of significance gave serious thought to what would happen if these fighters were actually to defeat the Soviets. What would happen then? Would all those fighters return home, spend the rest of their lives telling war anecdotes and living peacefully ever after? Or would they bring their Jihad back home with them?

As I mentioned earlier, the internal cold war within Islam played out in the Afghan theatre as well. Most Arab fighters who joined the Mujahideen were largely funded by Saudi-backed organizations. Many of these if not most operated under the Salafist ideology. On the other hand, Iran shares a major part of its eastern border with Afghanistan. It also shares some strong cultural ties with the local Afghan population in the Herat region. Therefore, it was an important priority for the Iranians to exert influence on political outcomes in Afghanistan. And so they too came and meddled with tribal relations; backed warlords who were largely associated with anti-Taliban forces known as the Northern Alliance.

Saddam’s Power Grab in Iraq: The enemy of my enemy is my enemy?

Another 1979 event that I find to be of relevance to contemporary Middle Eastern affairs is the accession of Saddam Hussein to the presidency of Iraq on 16 July of that year. Although many argue that he was in fact the country’s defacto leader for a few years prior to 1979, his accession to the presidency put him front and center within a region where power dynamics had seen a dramatic shift only about six months earlier. Saddam Hussein was a student of Gamal Abdel Nasser’s school of Arab nationalism. This would logically put him at odds with his rich Gulf neighbors and the U.S. So, how did a secular Arab nationalist with a socialist drive and Soviet connections find favor with the U.S. and the Gulf states? There is only one brief response to this question: Iran happened.

Recall that the Iranian revolution put in motion an internal cold war between the Saudi-led alliance of pro-western Arab regimes and Khomeini’s Iran. I also discussed how Iran became a ‘national obsession’ for U.S. policy makers in the aftermath of the hostage-taking and the anti-American hostility expressed by the Iranian regime. Saddam Hussein became an enabling vehicle for the anti-Iranian forces to limit the ability of the Ayatollahs to flex their muscle in the region. At any rate, the Iran-Iraq war was initiated by Saddam’s Command Council on 22 September 1980 when it attacked Iranian military targets.

The accession of Saddam Hussein to the presidency of Iraq in 1979 complicated the political landscape in the region and set the stage for future destabilization and turmoil. The U.S. policy towards Saddam’s regime in the 1980s was diametrically opposed to the one it put into action in the 1990s. This huge inconsistency, which many in the U.S. explain on the basis of U.S. strategic interests, has created a credibility gap for the U.S. in the Middle East, one that the Islamic militancy movement continues to exploit.

One question we must seriously ask ourselves in the realm of public policy and international relations should be: is the enemy of my enemy really my friend or an enemy waiting to happen? Or are alliances of convenience, what some would call ‘unholy’ alliances, really a good idea for the long term. To believe Alexis de Tocqueville: “In politics shared hatreds are almost always the basis of friendships.”

Conclusion:

Albert Einstein once said that “all of us who are concerned for peace and triumph of reason and justice must be keenly aware how small an influence reason and honest goodwill exert upon events in the political field.” In history we see folly and turmoil that could have been avoided and wisdom that could have been duplicated for the betterment of humanity. Many would say that hindsight is always 20/20. Yet, if it is so, one may ponder, why is that hindsight not our foresight; why is reason so hard to prevail in the pursuit of justice. I do not wish to simplify what is the complex nature of human interaction, but I remain convinced that we have the capacity to turn ignorance into enlightenment so as to condemn violence to the ash heaps of history.

1979 is a year we must all remember, if only for the seeds it planted and for the lessons it holds. As I mentioned earlier, the events of that year did not take place in a vacuum. The seeds of such events were also planted years, if not decades earlier. And if wisdom were to prevail, seeds of poison may no longer find fertile ground as they did in Afghanistan, Iran, and Iraq in 1979. If reason were to prevail, seeds of hope will instead be planted, the fruits of which the world community can proudly look forward to.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home